By J. Irving ft. Generative Pre-trained Transformers

Ipil had already learned how to whisper before it learned how to scream.

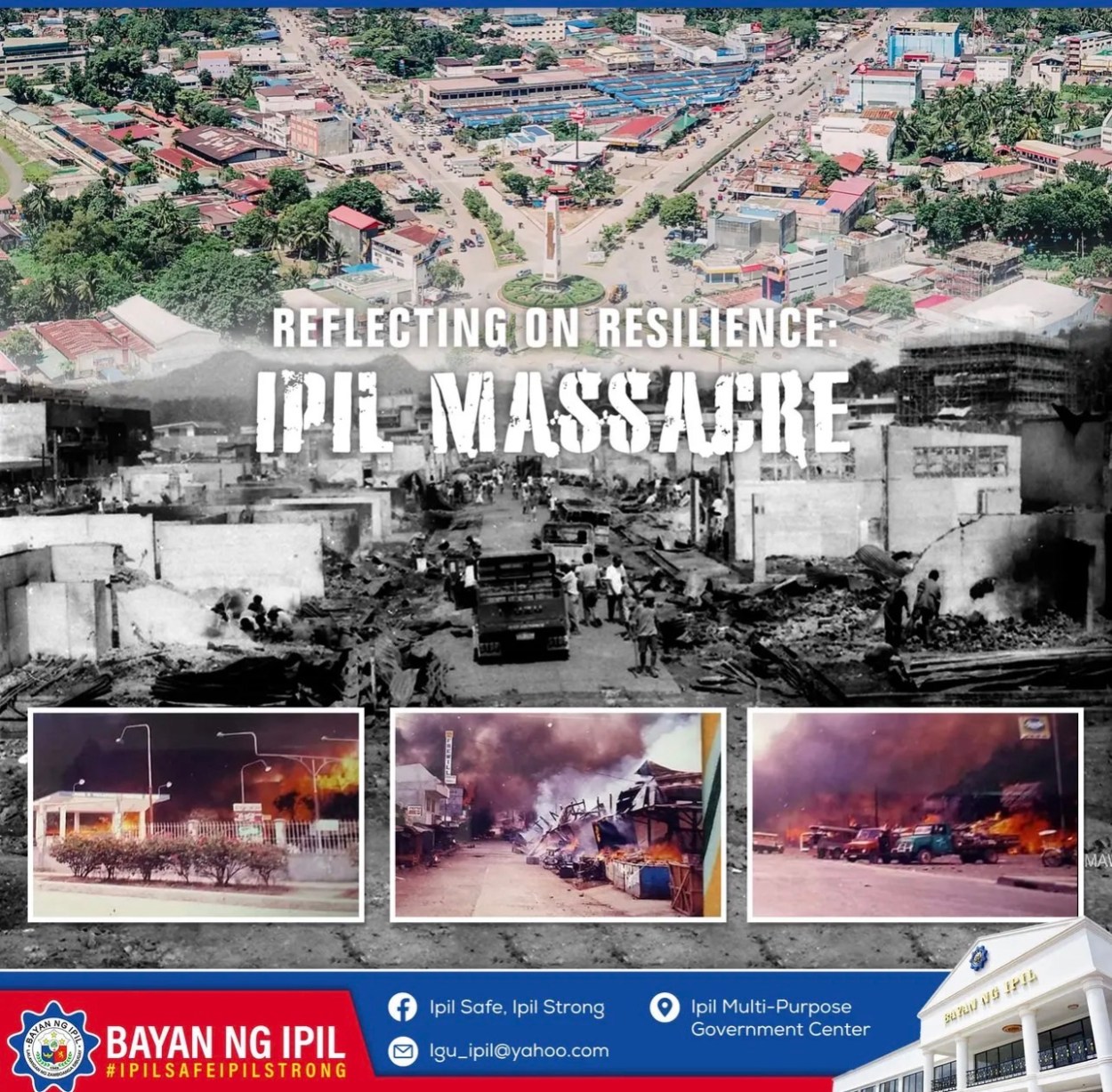

In the weeks before the massacre in 1995, fear moved quietly through the town—passed from market stalls to parish pews, from fishermen to teachers. Men with guns had been seen too often, their faces hidden not just by scarves but by the silence of those who dared not ask questions. Everyone knew something terrible was forming, but no one knew when it would finally break.

Bishop Federico Escaler knew.

As shepherd of the prelature, he had refused to close his eyes. He listened—to widows, to farmers, to young men who feared being taken in the night. He spoke openly against lawlessness, against the growing brutality that treated Ipil as a bargaining chip between armed groups and a distant state. And because he spoke, he was marked.

The attempt to abduct the Bishop was not an isolated crime. It was a warning.

When the gunmen seized him in 1985, it was meant to silence more than one man. It was meant to tell the town: If we can take your bishop, we can take anyone. But the rescue that followed—swift, violent, and desperate—disrupted more than their plans. It humiliated the perpetrators. It exposed their presence. It forced them into the open.

And for that, Ipil would pay.

The soldiers who moved to recover Bishop Escaler did so knowing time was measured in minutes, not hours. The jungle closed in as it always did—thick, unforgiving, indifferent to prayer or rank. Shots echoed, commands were shouted, and somewhere in that chaos, the Bishop was pulled back from the edge of disappearance. Alive, shaken, but unbroken.

The town rejoiced quietly. Too quietly.

Because vengeance does not announce itself.

A decade later, it came in daylight.

The massacre was methodical. Homes were entered, bodies fell where people had once eaten and slept. Fire consumed what bullets did not. The attackers were not there to fight soldiers; they were there to punish a population. Nevertheless, Major David Sabido ‘78, the commanding officer of the 10th Infantry Battalion of the Philippine Army, was among those killed, while he was eating in a restaurant.

Col. Roberto Santiago “68, commander of the 102nd Infantry Brigade based nearby, lost face and the incident becomes his Waterloo. He was a CGPA in waiting and never recovered.

The message was unmistakable: “You were protected once. You will not be again.”

The victims were not combatants. They were mothers, fathers, children—people whose only crime was living in a town that refused to fully surrender to fear. Their deaths were the final sentence in a declaration already written when the Bishop was taken.

In the aftermath, some said the massacre was inevitable. Others said it was unrelated. Both were wrong.

The rescue of Bishop Escaler and the massacre of Ipil were chapters of the same story—a struggle over control, dignity, and defiance. One act challenged the power of terror; the other sought to restore it through blood.

For the soldiers who had pulled the Bishop from captivity, the guilt lingered. Victory in one moment did not prevent tragedy in the next. Saving one life did not save a town. Yet the rescue mattered—not because it stopped the massacre, but because it revealed the cost of standing up to evil and the price paid when the state arrives late or leaves too soon.

Ipil remembers both days.

The day its Bishop was taken and returned.

And the day its people were taken and never came back.

Between those two days lies the truth: that violence is never random, that silence invites cruelty, and that courage—whether by a priest who speaks or soldiers who act—always threatens those who rule by fear.

And that is why they killed.

CSAFP General Sobejana and the AFP Committee for Awards and Decorations, particularly the MOV Board members, do not know their history – they consider the feat done by Lieutenant Bolo, in rescuing Bishop Escaler and eight others inside the stronghold of the MNLF and Abu Sayyaf, was very ordinary, as easy as it seemed. Just plain lucky!