By J. Irving

II Timothy 4:7 “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith.”

ABOUT THIS BOOK

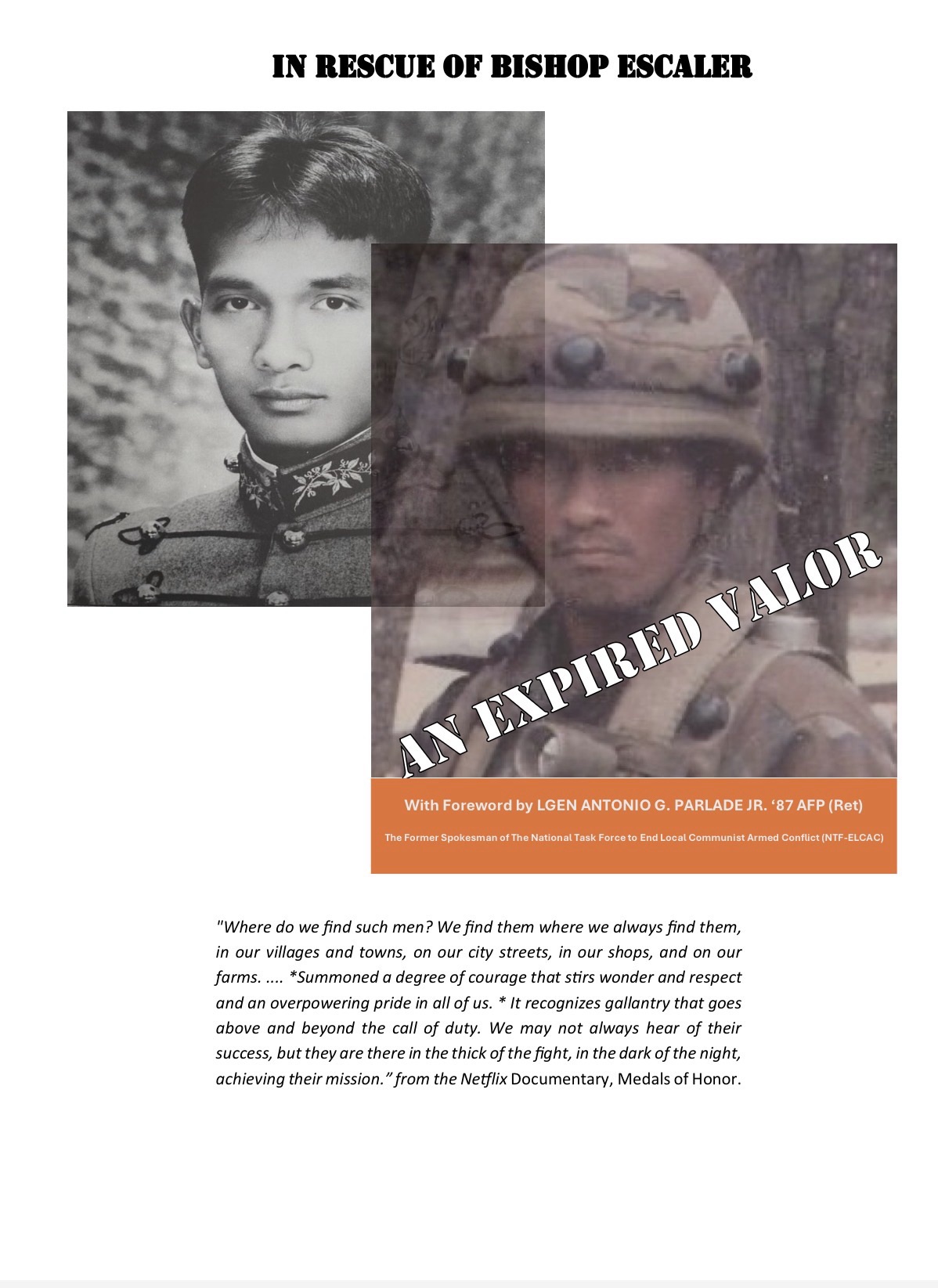

This is a story about the kidnapping and rescue of the late BISHOP FEDERICO O. ESCALER, S.J., when he was the curate of the Diocese of Ipil in 1985. He was abducted together with eleven companions; brought and held as hostages by the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) inside their stronghold. A surreptitious, daring and relentless pursuit was launched beyond enemy line, unfamiliar terrain and outside their Operational Area of Responsibility (AOR), by a team spearheaded by:

FIRST LIEUTENANT SEGUNDO “BOY” BOLO O-8071 (INF) PA

33rd Infantry “Makabayan” Battalion, Philippine Army

Even though the Medal of Valor (MOV) was denied, the author intends this book to serve as an inspiration to all soldiers, both officers and NCOs, and to aspiring ones who are intending to join the noble profession of soldiery.

The size of the book is 4” x 6.87”, enough to fit in the BDA uniform cargo-pants side pockets, so that the book can ably be carried around for reading and as reference, without much hassle.

The book is a first-hand account from Lieutenant Bolo himself, retold several times in drinking spree, among “band of brothers” – his Mapitagan Mistahs. The author is one of them who firmly believes that Bolo deserves the MOV award.

What was said is true, nothing but the truth because the retelling was the same as in the previous gathering – no braggadocios or bravados. In this matter, in writing down the story, the author decided to use the second-person narration, divulging Bolo’s thoughts on such heat of the moment, to create a specific narrative effect in disputing the accusation of the members of the MOV Board that the action of Bolo is not a SINGULAR ACT.

Placing the story in second person, the reader can imagine, himself, in the shoes of Bolo – feeling that every step of his choices and decisions was his burden, in the pursuit of the mission. Those choices are the decisions of Bolo, alone. This approach, where the narrator addresses Bolo directly, is used to frame his actions as if they are being interpreted or be judged without nuance.

The writer of this book is a constant drinking buddy of Bolo at numerous occasions, a survivor of the Pata Island massacrer, with other mistahs from the ground troops, the Army and Philippine Constabulary (PC); the same people who took the Scout Ranger Orientation Course (SROC) after graduation from PMA in 1980 and before their deployment to the front lines.

The Escaler story was foretold several times, repeatedly. I can attest that everything Bolo said in this story is true. Bolo has the same narrative every time he gets excited. I believe that it is difficult to repeat a lie, especially if intoxicated.

Likewise, Bolo chose me for my credibility. I can relate and emote the same feelings he was exposed in fighting the MNLF.

The reclassification of the Gold Cross Medal to the Medal of Valor (MOV) was denied and “Decided with Finality” during the term of GENERAL CIRILITO E. SOBEJANA ’87 AFP, as Chief-of-Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and who is a MOV holder himself.

So, during the evaluation, the MOV Board concluded and wrote Bolo directly that the documents presented did not meet the fundamental parameters required for the award – the SINGULAR ACT. Likewise, the prescription period of three (3) years was applied retroactively, even the ruling was implemented only in 1992; and the act of valor of Bolo happened in 1985. Thus, Bolo’s acts of valor had expired. In this manner, I am entitling the book as an “EXPIRED VALOR”.

I intend this book to be the reference for the Philippine Congress to reopen the case. The finality of the decision falls and may only end in Congress. It must take an act of Congress to waive the time limit and allow the award.

There are so many stories where some brave hero decides to give their life to save the day and because of their sacrifice, the good guys win, the survivors all cheer and everybody lives happily ever after. But the hero never gets to see that ending. They’ll never know if their sacrifice actually made a difference. They’ll never know if the day was really saved. In the end… they are broken.

WHY JUST NOW?

Many asked me, “Why just now? Why are you so passionate to recommend Boy Bolo for the Medal of Valor when the three-year prescription period has already lapsed?”

It was not an easy question to answer. Time has its way of dulling memories, but not the truth. The deeds of valor, no matter how long ago they were done, remain etched in the hearts of those who witnessed them. Some acts of heroism are so selfless, so pure, that they transcend the limits of regulation and time.

During the term of General Delfin Castro as Commander of SouthCom, two unforgettable events scarred and shaped the military landscape of that era: the Pata Island Massacre and the rescue of Bishop Escaler from the hands of the MNLF. I was involved in the first; Boy Bolo, in the second. Both incidents tested courage beyond measure. We were young officers then driven by duty, not by desire for fame or medals. Recognition was the farthest thing from our minds. We were soldiers simply doing what must be done.

When I look back now, I realize that time did not erase the weight of what Boy Bolo accomplished. The rescue of Bishop Escaler and ten others—without a single casualty among the hostages or his troops—was an act of leadership, bravery, and precision that stands as a model of military heroism. Even General Castro considered Boy Bolo as lucky.

It was courage guided by duty, compassion, and faith.

Why only now, then? Perhaps because only now, in the calm of later years, can one see clearly what the fog of youth once hid. In the rush of duty, we brushed aside recognition as something unnecessary, even embarrassing. But with age comes perspective. We have learned that remembering and honoring valor is not vanity—it is justice. It is an obligation to truth, and to the generations who must know what true service and sacrifice mean.

Boy Bolo never asked for honor. Like many of us, he did his duty quietly and moved on. But silence should not bury greatness. Even if rules of time have expired, moral duty has not. The Medal of Valor may be bound by regulation, but valor itself knows no prescription period.

As I now stand in the sunset of my years, I thank the Good Lord for keeping me alive to tell and write these two stories—the one of tragedy and the one of triumph. I do so not for myself, but for a comrade who carried the weight of courage with humility.

Boy Bolo deserves the Medal of Valor not because of what he sought, but because of what he gave— his heart, his bravery, and his unyielding faith in his mission and men.

Some may ask again, “Why only now?”

Because now, more than ever, truth deserves its time.

F O R E W O R D

By LtGen Antonio G. Parlade Jr., AFP (Ret)

LEST WE FORGET.

This was one truly valorous feat of the Army and AFP. It became the standard until MILITICS got the better of us.

So, when the senior AFP leadership then experience “drought” in accomplishments they simply manufactured one.

That made the Commanders “pogi” (Good Looking) to the seniors, to the bosses, but at the expense of those who truly deserve the Medal of Valor (MOV), or even lesser awards.

LT BOY BOLO would have been one of them.

Yet those who eventually get the MOV, even if not deserving, have one common denominator – ambitious commanders.

Ambitious for higher command positions, never mind if they lie to their teeth about the narrative and the “circumstances” around the specific feat of Valor in question.

So, madaming naging “valor-valoran”. Pinalusot ang isa, nasundan pa ng iba.

Kumobra ng libo-libong incentive pay. Pumila sa mga schooling abroad at iba pang benipisyo.

At pagdating ng araw, pumila na rin para maging CGPA at Chief of Staff AFP. Hindi na nahiya.

Yes, the MOV is an institution in itself.

We respect the institution, but sadly we cannot respect some individuals whom we knew later on to be a FRAUD.

Ito ang masaklap sa kwento ng idol kong si Lt Boy BOLO.

Hindi man sya SF or Ranger but he deserves my snappiest salute!!!

A PRELUDE

This is one of combat exploits of Boy Bolo that also needs to be told, to support my claim and recommendation for his MOV. It happened before he was deployed to Ipil. He is a true living hero, in the eyes of the Philippine Constabulary.

The daring action happened in Barangay Ligaya, Llanera, Nueva Ecija, sometime in 1983. Retired Police General Hermogenes Ebdane ’70—now Governor of Zambales—can attest to this; because at the time, he was the Philippine Constabulary (PC) commander of Task Force CABNET (Cabanatuan), an all-out counter-insurgency operation against the New People’s Army in Central Luzon.

Your unit Mistah Boy, the 33rd Infantry “Makabayan” Battalion, had just arrived in Nueva Ecija, fresh from sustained combat in Sulu and Mindanao. In the area, you were reunited with a kind and generous upperclassman from the academy, a PC officer, Jaime Tagaca ’77—the trusted sidekick of Major Manuel Divina ’73.

One afternoon, Tagaca broke radio silence. There were no cellphones then. Only static, urgency, and fear. “Boy, reenforce mo kami!” he shouted over the tactical radio. “Pin down kami! Ang dami nang wounded sa tao ko…” (We’re pinned down. Too many wounded.)

“Sir, hindi ako maka-alis,” you replied. “May operation din kami. Taong-bahay ako. Nasa labas ang buong tropa.”

“I don’t care. Puntahan mo ako. Ngayon!”, Tagaca ordered.

“Sir, sige,” you answered. “Dala ko na lang ang naiwan—clerks at cooks.”

What Tagaca did not know was that these “clerks and cooks” were battle-hardened veterans—men who had fought the Tausugs in Jolo and lived.

You scraped together thirteen men. You rolled out with your men in two military jeeps. When you reached their position near the highway, the scene was grim. Everyone was flat on the ground, faces pressed into the mud, firing sporadically – careful, afraid to expose themselves. Tagaca crawled toward you, soaked in mud and sweat.

“Boy, mortarin mo na!” (Use your mortar).

“Sir, wala akong dala,” you lied. “Saan ba sila? Wala akong makita.”

You actually brought a mortar but you didn’t want to use it. You left the mortar-man with the vehicles but left instructions to watch, if ever you would need mortar support.

“Doon!” Tagaca hissed. “Sa irrigation canal.”

The battlefield was a nightmare—flat rice fields as far as the eye could see. No high ground. No cover. Only open space and death waiting to happen.

“Ahh, madali ’yan,” you said quietly. “Aassaultin ko na lang.”

Tagaca grabbed your arm. “Huwag! Mamatay ka diyan. Tingnan mo—ang dami ko nang wounded.”

“Hindi, Sir. Ako na ang bahala.”

You spread your men in a straight line along the roadside ditch. No flanking. No maneuver. Just speed, shock, and firepower.

Then you gave the signal. You all rose as one.

Rifles erupted in unison. You and your men advanced, firing continuously, aiming at shadows and movement erupting from the canal. The air was ripped apart by gunfire—and by your own shouting.

Then, PONG! “Baliktad si Gatchi!” You ran towards him. “Ano ’yan?”

“Tinamaan ako, Sir… pero buhay pa.” He stood up and continued shooting.

Magazine after magazine. No pauses. No mercy. Then—silence.

Fifteen minutes.

That was all it took. Tagaca’s men had been fighting for hours.

You were able to take the enemy position, your objective. Eight assorted high-power rifles, composed of M-16s, garands and carbines, lay scattered in the mud. You picked up the M-16 that came across you and gave it to one of your men behind, saying, “Eto, magpa-inom ka!” (a tradition in Tabak Division that a soldier who gets an enemy’s weapon will be automatically promoted to next higher rank).

Only one of your men went down—the driver, Gatchalian.

Then came the part no after-action report ever submitted.

During the search, Sergeant Amora froze. A girl sat on the ground, hugging her knees, crying uncontrollably. Blood ran down her shattered kneecaps.

“Sir,” Amora whispered, raising his rifle. “Kasali ’yan. Barilin na natin.”

“Babae ’yan,” you snapped. “Ano ka ba?”

She was shaking. Broken. Terrified.

Later, you learned the truth. She was the sister of one of your soldiers. Her mother had been searching for her for three months. She had been sent to a state university in Nueva Vizcaya; and no one knew she had joined the NPA. Her surname was Arenas.

Had you not been there, she would have just been an additional stat in an AFP insurgency report.

“Huwag n’yo patayin,” you ordered. “Ipapagamot natin ’yan.”

When brother and sister saw each other, they collapsed into each other embrace, crying like characters in a telenovela—except this was real.

The war spared her.

The story, most likely, had a happy ending: the former NPA amazon later fell in love—with a soldier and married him.

For this unselfish act of valor, Lieutenant Bolo was awarded with his first Gold Cross Medal.

AN EXPIRED VALOR

THE ABDUCTION

It was a quiet February 22nd morning in 1985 when Bishop Federico O. Escaler of Ipil Diocese, a mild-mannered Jesuit, boarded a Ford Fierra van with ten companions—three nuns, two teachers and five lay church workers—on a pastoral mission in the troubled region of Tungawan, Zamboanga del Sur, deep in the southern Philippines.

Their journey, meant to be one of service and hope, was suddenly cut short.

As the van rattled along the dirt road, it was stopped by armed men—rebels, members of a Moro separatist group. With rifles slung over their shoulders and eyes hardened by war, they ordered everyone out of the vehicle. The group, stunned but calm, did as they were told.

“Everybody out!”

Bishop Escaler stepped out, calm but cautious. He could see it in their eyes: this wasn’t a random checkpoint. This was a planned operation. Meliton, the driver, was trembling. The bishop placed a hand on his shoulder, steadying him.

Without further warning, the eleven were seized, blindfolded, and hurried into a waiting vehicle. The world outside dissolved into motion and muffled noise—the crunch of tires on gravel, the buzz of insects, the occasional shout from one of the captors.

They were marched off into the jungle from where they were abducted. When the blindfolds were removed, the bishop found himself in a remote place deep in the jungle. Rough tents, hammocks, and young men with weathered faces filled the clearing. Some looked barely out of their teens. These weren’t regular soldiers. They were members of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) —armed, organized rebels, or possibly rogue militia. No insignias. No laws. Just guns and silence.

Bishop Escaler, then 63, was no stranger to the dangers of Mindanao. The island had long been torn by conflict—Muslim separatist rebels waging war for independence from the central government, military units sweeping the countryside, and civilians caught in between. But even he hadn’t imagined that on this day, he and his companions would become hostages.

Later, that same day, a Friday, at about 10 o’clock in the morning, Fr. Montecalvo from the Bishop’s palace went in a hurry to the headquarters of 33rd Infantry “Makabayan” Battalion (33IB) at Ipil. The priest broke the news and reported that Bishop Escaler, the Bishop of Ipil, was kidnapped in Tungawan by unidentified armed group. You were there Boy, as you usually man the Tactical Operations Center (TOC). The priest was requesting for immediate assistance in form of a military action to recover the bishop. You and the other people at the battalion who heard the news quickly assumed that the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) did it. The secessionist group lords it over Tungawan. The place is their Area of Operations (AOR) and stronghold. When the priest left, Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Sangalang, the Battalion Commander (BatCom) of the 33IB, met you and other key Officers and NCOs, to decide on your unit’s courses of actions. You were hesitant though, together with the other officers, to act. Fr. Montecalvo, the one who asked for help, and including the bishop were anti-military. The clergies of the area were even publishing articles against the Army; and there were reports that subversive journals were being printed in their parish. Colonel Sangalang, however, was a good public relations (PR) person and told you, “Kaibigan natin si Bishop, Boy” (The Bishop is our friend, Boy). The BattCom used to kiss the bishop’s ring and deeply respects the prelate. You were very reluctant to act because the people, whom your commander was supposed to be saving, were all bad mouthing the military; and the area where the bishop was abducted and to be pursued was already outside your battalion’s AOR; particularly, the place of abduction was not within your AOR where you do not need to react and just let the troop responsible to answer do their job. The area belonged to the local Philippine Constabulary (PC) unit; and coordination with different branch of service would be difficult. Moreover, the battalion also had little or no intelligence at hand of the kidnapping and not familiar with the area.

Nevertheless, Colonel Sangalang was very diplomatic. He was a typical Batangueño, in his words and action. Everybody referred to him, at his back, as “Balisong” (the well-known butterfly fan-knife of Batangas), which he always carried in his pocket. Sangalang has the reputation of being courageous, outspoken, and assertive. He is often described as “palaban” (ready to stand up and fight for what’s right). For instance, when he assumed command of the battalion, nobody dared anymore calling his 33rd IB as “taray-taray” (an ilocano word for someone who runs away from a fight); a monicker earned by the previous commander when his troops withdrew from a firefight. The word rhymes with “thirty-third”. Despite his palaban attitude, he was known to be hospitable, friendly, and welcoming, especially to visitors, typical of a Batangueño character. Colonel Sangalang, by the way, was one of legendary General Canieso’s dependable field commanders. The Batangueño is battle-tested and battle-hardened in Jolo where he served General Canieso as his Brigade Commander.

One time at TOC, when his troops were engaged in a firefight. He called you Boy, “Come here Boy – watch and learn.” As he directed his troops by radio what to do while directing mortar fire support. Colonel Sangalang were very cool – stable while under pressure, always concern about the best safety for his men in accomplishing a mission.

For this matter, Colonel Sangalang, in all his wisdom decided to move the troops despite hesitations of everybody. He said, “We are the largest and nearest combat unit to Tungawan and very likely, we will be asked soon by higher headquarters to respond as the news would reach them.”

Colonel Sangalang, the battalion commander dispatched you immediately, as head of the Striking Force. You can move very fast, a marathoner during your cadet days, through the undergrowth down the valley —boots sunk into the leaf-litter, bolo (no pun intended) swung to clear paths — while the rest of the platoon fanned out behind you. Your radioman carried a pack; your lifeline was strapped to the back of your favorite radioman: the PRC-77. He went with you wherever you go out of your base camp on patrol. He was your shadow, always at arm distance, but surreptitiously far away, in the open field, not to identify you as the team leader, for enemy snipers to target you first.

To civilians who hasn’t seen one up close, the PRC-77 looks like an honest, unpretentious piece of kit — a rectangular metal box in olive drab, the edges nicked from years of being set down on rocks and truck beds. The harness bites into the shoulders of the radioman but steadies the load. A long, dark whip of an antenna screws into the top and trembles when walking, a rigid spine that turns every step. The handset hangs within reach, its cord coiled like a telephone from another age; when the Press-to-Talk (PTT) button is pressed, the radio answers back with a small, mechanical static sound, with voice messages.

You arrived Tungawan with about two platoons and an armored personnel carrier (APC) which came simultaneously passing along the streets. You found the white Ford Fiera with flat tires that was used by the bishop and ten other passengers. In your hasty intelligence gathering, you found out that the MNLF was supposed to kidnap a rich businesswoman in Ipil, named Delos Reyes, who also has a white Ford Fiera. The abductors did not know who was in the vehicle and learned only when the bishop introduced himself. The Escalers were the owner of Pepsi Philippines during that time and abductors realized they have a potentially lucrative target of opportunity.

You talked to the commander of the nearby PC detachment, a constabulary lieutenant. The lieutenant related that his men were able to respond quickly and tried to pursue but were repulsed violently by heavy machinegun fires, believed to be M60. Outnumbered and outgunned, he decided to withdraw back to the highway after a short pursuit. You were about to tease the PC officer by asking, what happened to your battle cry: “Always outnumbered but never outfought”?

As the night was falling, the two platoons under you proceeded to an old, abandoned logging base in Cayamcam. You were serving officially as Hunters’ Company Commander (Striking Force) but acted as S2/3 (Staff for Intelligence and Operations) and platoon leader for critical missions as directed by your Battalion Commander, for the reason that the unit lacked officers and the few had to handle multiple designation. You decided to stay there for the night.

At night, when the jungle turned cooler and the insects began their ceaseless orchestra, you thought about what the PRC-77 does and doesn’t do. It is simple and faithful: VHF, FM, voice. When the cloud canopy opened and the moon found gaps between branches, voices carried clear across the valley; when you climbed a ridge earlier, the signal jumped like a stone across water, touching the command post. On a clear day, with the antenna high and no hills in the way, the radio can reach far enough that your words bridge platoons. But in dense green, the distance range shrinks, the world folding in until the voices come thin and creased. You learn the terrain by how the radio behaves if your words arrive or don’t.

The front panel of the radio is a study in practicality. Knobs for volume and squelch, a rotary dial for the old, familiar channels, and sockets that have seen hands both careful and hurried: the handset jack, the antenna fitting, a plug for an external speaker. There’s no glossy screen, no glowing map—just metal, switches, and the honest click of mechanics. You don’t ask the PRC-77 for stealthy encryption or silent broadcasts. You ask it to speak clearly, to survive a rainstorm, to let you call in a casualty or ask for a bearing. It answers in radio-signal honesty.

Batteries are a constant negotiation. Your men carry spares in a poncho liner, wrapped in plastic to keep the damp from leaching at their strength. Sometimes the nights were long and the comms longer, and the pack gets heavy with both the weight of the set and the weight of responsibility: a platoon’s eyes forward, a team leader’s report, a medevac call. When the battery meter dips, you feel the urgency—conserve. When it’s full, there is a small, private comfort: enough juice to make it through another patrol.

There are accessories, the small comforts of preparation: an external loudspeaker for addressing a sleepy checkpoint without dragging the handset from its holster; a field mast and an antenna mount when we rig to a vehicle and try to make our words fly further; spare crystals and test gear tucked away for when a dial decides to be stubborn. Each add-on is an attempt to coax more from something stubbornly analog, to extend a human voice across a terrain that seems determined to swallow it.

During that particular patrol, the jungle swallowed a message mid-sentence. You remembered the sudden static and the way your commander’s voice broke like a shy animal. You stopped, all of you, and listened. The PRC-77 hung mute for a moment in your hands as if it too were holding its breath. Then with careful adjustments to antenna height and a quiet, steady voice over the handset, you bridged the gap. No miracles—just patience and the right angles. It’s the sort of thing you learn how to make an old radio perform as if it were new again.

There are limitations, sure. The radio can be intercepted; the jungle doesn’t care about your secrets. It can be jammed or listened to, and it bursts with the truth of analog voice—every laugh, every cough, every tremor in command. And compared with newer kits, like the Harris Radios of today, it is bulky, heavy, and blunt. But those very things are also its virtues. It is straightforward to fix with a small kit and a steady pair of hands. It is not afraid of mud and rain and being dropped. For men who have to move light but think heavy, it is the kind of tool that grinds its way through practical problems without grand promises.

The 33IB established security defense and prepared for the next day. During the night the people at the battalion were seeing distant lights from the jungle as they hoped for the safety of the hostages. While staring at the lights, the battalion commander radioed you, “If sila yun Boy, i-rescue na ba?” (If it is them, do you have to rescue them already?). You answered, “Yes Sir !!!”

TROOP BUILDUP

The bishop and hostages were taken deep into the jungle. The bishop and several of his companions were forced to march through thick undergrowth. Some were released early, especially those two who couldn’t walk. One was pregnant and one weak lady to act as companion; but Escaler and others — including some of his staff — were kept.

Meanwhile, back in Ipil, word of the kidnapping reached the Church and the military – even worldwide in international scene. The news spread fast. A bishop had been taken. The military launched a massive response. Troops were mobilized, helicopters readied, and two navy patrol boats were deployed to guard the coastal escape routes.

In the dense jungles of Tungawan, the bishop’s captors tried to stay hidden. But the noose was tightening. The military had surrounded the area. Over a thousand soldiers, backed by helicopters and river patrols, encircled the region. Escape was becoming impossible.

At the same time, church leaders — fellow priests and even relatives of the kidnappers — were working to open lines of communication. They pleaded for the hostages’ release. They warned the captors: the army was coming. Blood would be spilled if they didn’t let the bishop go.

But the rebels held on, hoping to use the bishop as a bargaining chip. What they didn’t know was that the soldiers were already close.

At daybreak, you used the PRC-77 to call in your 10-20 (location). The voice on the other end had the sleepy cadence of someone waking to radios and coordinates. You keyed the handset, spoke your position, and watched the antenna bob as if it, too, were listening. The answer came back and the platoon relaxed a little — rucksacks shifted, shoulders eased. Small things, but all matters.

When your radioman put the radio down for a 10-minute break, you ran a hand over its case. There are scuffs like stories and a handle worn from many palms. It is not the cutting edge of modern military tech, but it is honest and dependable. In the quiet before you stood up, you imagined the metal box as a sort of necessary spine for your little world out there in the jungle —a tool that holds a thread of human connection across hills and rivers and the long, indifferent green.

In the end, the PRC-77 isn’t just hardware. It’s part of the rhythm of patrols, the punctuation of orders, the heartbeat of contact: a stubborn, reliable speaker of human things in a place that otherwise has no language but rain and leaf and silence.

For three days, troop buildup was happening. The SOUTHCOM already learned of the incident when the battalion sent a spot report the night of Day-One. In Zamboanga City, Major General (MGen) Delfin Castro, the Commander of the Southern Command (SouthCom), briefed the media and church leaders about the incident the following Saturday morning. Present were Archbishop Francisco Cruces of Zamboanga Diocese and Atty. Manuel Escaler, the younger brother of the bishop. In Manila, the Acting Chief-of-Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), General Fidel Ramos, who ordered all available military and police in the area to conduct search and rescue. On that same day, at Cayamcam Base, there was so much chatter in the UHF187 tactical radios with SOUTHCOM base. Soon two UH1H Helicopters, also known as Hueys, arrived in the area. The passengers were very senior commanders: Colonel Ernesto Calupig of the Special Forces, Colonel Romeo Abendan of the Ninth Regional Unified Command (RUC9) and Major General Delfin Castro, the SOUTHCOM Commander. The mayor of Zamboanga City, Mayor Manual Dalipe, was also there. 33IB had already deployed patrols around the area to pursue and look for clues of the whereabouts of the hostages and their abductors.

On the succeeding couple of days, the SOUTHCOM Commander brought in one company of Scout Rangers and one Company of Special Forces under a certain Lieutenant Dela Cruz. The troops were immediately deployed in areas the brigade assessed to be potential routes of the kidnappers. More troops were brought by the 301st Brigade Commander Colonel Maderazo. Even Assemblymen and politicians were already in Cayamcam to know firsthand what’s happening. Pinpointing the MNLF group’s location was getting bleaker as the days passed by.

Local officials, who were familiar with the terrain, were brought in but the information they gave were not of value and very little usable intelligence.

When you said, enemies have the master of terrain. It typically means they possess superior knowledge, control, or utilization of the local geography compared to government troops. The term often arises in the context of guerrilla warfare, resistance movements, or insurgencies.

The key implications of rebels having mastery of terrain, means:

- They have the TACTICAL ADVANTAGE where rebels can exploit natural features like mountains, forests, caves, or urban settings to stage ambushes, evade capture, or launch hit-and-run attacks; their intimate knowledge of trails, choke points, and hidden routes gives them mobility and surprise.

- In ASYMMETRICAL WARFARE: even if the rebels are outgunned or outnumbered, terrain mastery helps level the playing field; historically, insurgents in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Latin America used their environment to resist larger military forces.

- Supply and Communication Lines: control or familiarity with the terrain allows rebels to establish secure supply routes and safe havens (e.g., mountain hideouts, jungle camps); they can also disrupt enemy logistics more easily.

- Civilian Support: often, such terrain advantage is bolstered by local population support, who may provide shelter, intelligence, or logistical help.

As the different commanders continued to send patrols, the thick jungle all the way north to Zamboanga del Norte seem hostile and uncooperative.

THE KIDNAPPED VICTIMS

One of the patrols in pursuit managed in retrieving two elderly hostages who were left behind apparently since Ms. Teresa Molina and Ms. Lilia Ignacio, both public school teachers from Zamboanga City, became ill. From them, it was learned there were nine (9) remaining hostages, namely:

1) Most Reverend Bishop Federico O. Escaler, a Jesuit;

2) Spinola Sister Nilda Palad, who works in the prelature;

3) Jeanette Loanzon of Grail International, principal of the night high school at Marian College and chief officer of the adult education program in Ipil;

4) Ms. Flordeliza Napigkit, the bishop´s secretary;

5) Ms. Jenny Sanoy, faculty member at Marian College;

6) Ms. Josefina Narciso, who works with Oblate Fathers in Bongao, Tawi-Tawi;

7) Joel Porras, a Marian College high school student;

8) Rene Egno, another Marian College high school student;

9) Mr. Meliton Quizon, the bishop´s driver.

According to the two women, the abductors were estimated around 11 fully armed men. They also witnessed the killing of three shrimp fishermen who were shot to terrorize them and on the other hand, prevent the dead fishermen from reporting the route of the abductors and giving clues to their identities.

In Jolo, Moslem separatists were also holding kidnapped victims: John Robinow, a New Yorker and Helmuth Herbst, a German from Munich for three months, since November 19, 1984, for ransom payments.

THE GREAT PROVIDENCE

On day four, the 26th of February, a Tuesday, at dawn, one patrol leader, First Lieutenant Sammang Abubakar, who is the Headquarters & Headquarters Company Commander of 33IB, called the Tactical Operations Center that he noticed tracks that were trodden by many hikers. He reported he could not confirm if these were tracks of the kidnapped group. They followed the tracks for a short while but stopped when it pointed to a deep ravine towards the river. Colonel Sangalang called you, “Puntahan mo nga Boy! Ikaw ang mag-confirm kung sila nga yon o hindi” (Go to the place, Boy, and confirm if they are the ones or not). You immediately left the base along with two men, one soldier (your PRC-77 radioman) and one, a CAFGU, a native of Ipil, who is very knowledgeable of the place. You broke through the thick jungle and managed to rendezvous with Lieutenant Abubakar. When you arrived the location, you too cannot confirm if these were the tracks of the hostages and their abductors. You then called Colonel Sangalang and told him, “Sundan ko na lang ito sir. Nandito na rin lang ako. Dalhin ko ilang tao ni Sammang.” (I’ll follow the tracks. Anyway, I am here already. I’ll bring some of the men of Lieutenant Abubakar). At that point, the group were very low on food and supplies and were very hungry and tired. Some were injured during the night patrols and were limping. You then announced, “Yong puwedeng sumabay sa akin na malakas pa, sumabay at hahabulin natin ito. I-engage natin habang may daylight pa. Kung hindi natin hahabulin ito, mawawala na talaga sila!” (Those who can catch up with me and still strong, come with me and we will run after them. We will engage them while there is still daylight, if not, they will be truly gone). So those who cannot keep up and follow were allowed to go back to base. You brought with you all of the four (4) Igorot Ranger trackers from Lieutenant Abubakar’s men.

There were eight people, a squad strong, who went down with you that ravine to follow the tracks half-running, half-walking. Just like Daniel Day-Lewis in the film, “The Last of the Mohicans”. Most of the time running but also walk when you and your men got tired but never stopping to rest. The movement was so repetitiously quiet.

When you reached a portion of the riverbank, there were signs that people slept there during the night from makeshift bamboo and leaves ground coverings. But most significant was that they found tissues/napkins. You immediately reported on the radio, “Sila na ito sir, wala naman MNLF na gumagamit ng napkins” (We found them Sir. There are no MNLF using napkins).

You hurriedly pursued but always keen on positively identifying the tracks and with very little noise possible.

The hostages had been very wise in providing clues by breaking twigs and leaving fresh leaves and tissues on the tracks. Although they were mostly treading on shallow waters, they manage to leave signs.

The tracks were getting fresher and fresher. But there were times when the tracks were unclear so your team had to completely stop and the four trackers would confer to decide on the most likely direction they went. You too would join the small conference analyzing signs, ask them individually of their readings just to be sure, and confirm the directions to take. The four must unanimously agree.

According to your understanding, you only agree before they all decided which direction to take.

Then, the trackers would see footsteps on top of the river rocks still wet and very fresh; your team can just imagine how close the hostages were, a few minutes ahead of you. If not, the footsteps would have dried up already as the sun is up. Most of the time, the abductees and abductors were in the creek and river water, making it difficult for anybody following them to detect their tracks. However, the four Igorots with you were experienced trackers and are really very good. They have gained their experiences mostly in tracking wild boars and evading enemy tribes.

Then, the trackers lead the rescue team to a very steep ravine infront of them that is very stiff and cannot see any passages. You talked to the four trackers and asked them again, “Saan sila nagpunta?” (Where did they go?) All four pointed upwards and saying, “Sir umakyat sila dyan!” (Sir, they climbed here). You asked them if they were sure and the four said, “Yes Sir!” So, you and your men climbed the ravine very silently, holding anything they can hold on, protruding rocks and deeply rooted stems, but wondering how the hostages were able to climb? They climbed with difficulty as the hill was almost vertical; and although there were small trees and vines to hold on, they just couldn’t imagine how difficult it was also for the hostages to reach the top. When the raiding team reached the top, it was a plateau, still thickly covered by vegetation and giant trees but there were big, elevated huts on the clearing under the trees. The huts were not ordinarily made with nipa but with wood. Perhaps, they were built that way over time. They now realized they are inside an MNLF Camp!

THE RESCUE

You ordered your men to deploy with maximum firepower facing the huts but to observe for a while. There was complete silence and there seemed to be no one around; but there was smoke in one of the huts very close to the team, about 6 or 7 meters away. Somebody must be cooking, you surmised. If this camp is occupied, you were looking at potentially an MNLF company or even more. But then, you must take the opportunity and better engage them in broad daylight otherwise your team probably won’t have the opportunity to do it anymore when darkness fell.

Suddenly, you saw a man with a slinged M16 rifle going down the stairs of the hut directly in front of you. You told Sergeant Amora beside you, who has a better view. “Muray, M16 O! Birahin mo na!” (Muray, he has an M16, shoot him!); before your presence and location was compromised. That started the firefight! Everybody of the raiding team opened fire aiming on human targets moving infront of you. You can see and watched as the MNLF jumped out of windows completely startled at the burst of fire surrounding the huts.

Sergeant Amora, a veteran of several such missions, led the group with unyielding focus. His eyes scanned the terrain constantly, searching for signs of live targets —a narrowing in the creek, a fallen log that might provide temporary cover, or better yet, a trail that would lead them uphill and out of the camp. He knew that the rebels, familiar with the terrain, would try to flank them. They couldn’t rely on speed alone; they needed to outthink the enemy.

And perhaps in haste, the surprised enemy managed to grab their weapons only, without reserved ammunitions. You assumed that most were sleeping when the firefight started, except for that lone guard, as everyone in the camp were all, both the abductors and abductees, very tired from the long 4-day trek – resting and off-guard. Now, they were all scrambling and running for cover behind the trees and hiding in the vegetation.

The air was thick with smoke, dust, and the sharp scent of gunpowder as the sun dipped below the dense canopy of jungle trees. The once-quiet base camp, camouflaged gently through the heart of the forest, now bore witness to the desperate fight of a group of army troopers.

Moments earlier, your search had come under sudden doubt that you lost your quarry; but at that time you stumbled against a band of rebel fighters—your surprise attack was swift as it was violent. Caught off guard and unaware, your enemy had no choice but to run away into the wilderness, their survival hinging on their ability to outrun and outmaneuver you, as their pursuers.

THE RUNNING BATTLE

The captors splashed into a stream of water, your men pursued, the creek described by the bishop, the cold water biting at the boots of your men as they stumbled forward. The terrain was treacherous—slick rocks, tangled roots, and the uncertain depth of the stream slowed your progress. Mud clung to your uniforms, and branches clawed at their faces like the fingers of the jungle itself trying to push you forward. But adrenaline coursed through your veins, numbing your body pains and kept you pushing fighting.

Behind, the enemy, cracks of rifle fires from you rang out, echoing off the valley walls. The rebels were hit, though unseen, using the dense undergrowth to their advantage. The troopers dared not stop. Each step through the creek was a gamble: a twisted ankle, a misstep into deeper water, or an unexpected sniper shot could end their run in an instant. Their breathing grew labored, and the pack of gear on their backs felt heavier with each passing minute. Still, they pressed forward.

Suddenly, one of the older troopers, slipped on a mossy rock and fell hard into the shallow water, his rifle sinking partially beneath the water. Sergeant Amora turned back immediately, pulling him up by the strap of his vest. “Tayo ka! Walang ka tropa maiwan!” (Get up! We leave no one behind), he barked, though his voice was hoarse with exhaustion. The CAFGU nodded, eyes wide, his lips trembling not from fear alone, but from the cold water soaking through his fatigues.

They pressed on, the murmur of the creek their only constant companion. The jungle began to thin slightly, the trees no longer forming an impenetrable green wall. Amora spotted a break in the ridge—a narrow path rising up from the creek bank, overgrown but passable. He signaled to the others, and one by one, they scrambled out, boots squelching as they climbed. The steep incline was punishing, but every step upwards increased the distance between you and your preys.

As you have reached the topmost, the jungle opened into a small clearing, bathed in the fading amber light of dusk. The sounds of pursuit had faded. For now, the rebels thought they reached their comfort zone. The troopers were in high alert knowing you and your men entered an enemy camp; their chests heaving, their faces streaked with sweat, mud, and the grime of close combat. They were soaked, battered, and bruised—but alive.

Then from the hut nearest to you, out came a woman whom Muray was about to shoot; but you said, “Huwag babae yan!” (Don’t shoot! She is a woman). The woman crawled out followed by another woman, and finally the third person out of that hut was the bishop himself. This was the time you radioed your homebase the confirmation of the presence of the bishop. You actually saw him and you have to make your move. You immediately closed in and personally pulled the bishop and most of the hostages out of the hut under heavy gunfire.

You inverted your fatigue baseball cap with a black embroidered AFP logo, so the hostages can recognize and identify you as government troops. You told them, “Neng, kilala mo ako??? Kilala mo ako??” (Lady, do you know me? Do you know me?); and they responded, “Ay si Sir!!” (It’s you, Sir!). The lady happened to be the sister of your friend whom you frequented to hang out and play guitar with. You said, “Mga sundalo kami. Paspas, paspas! Let’s go!!” (We are soldiers. Hurry! Hurry! Let’s go!), as he pulled them out of the hut. When you saw the bishop, you called your battalion commander again, and confirmed to him that you personally has the bishop and held the handset for them to hear the firefight while shouting in excitement, “HAPPY NEW YEAR !!!” Your battalion commander replied, “Bahala ka na dyan. Ikaw and andyan . . .” (Take charge! You are the one there . . .)

Colonel Maderazo, the 301st Brigade Commander was so angry when the 33IB engaged the enemy, as he had given orders beforehand not to engage in order to give way for the negotiating team to talk to the bandits. The idea, that negotiations was going on, was to prevent you from pursuit, or at least minimize your military actions. The instructions turned out to be a blessing in disguise for the 33IB. You were all alone to make a fast break. So, other troops did not move, preventing mis-encounters with friendly units; because if there were so many troops in the same space of operations, there would surely be chaos among friendly forces wanting to get the credit of rescuing the bishop!

But the soldiers, whom you left behind and told to go back to your home base, actually followed you from a distance and within minutes, Lieutenant Abubakar’s two platoons (minus) were able to join the firefight. “Nahiya silang umuwi, sa isip-isip mo. Kahit pagud at injured na yun iba. May nahulog sa pag-akyat ng ravine at napilay.” (Some felt guilty, as you surmised. Even though tired and injured; and there were who fell in the ravine and got crippled.

You let your soldiers fire their M203’s directed at locations where heavy gunfire emanated to show superiority of firepower.

While the firefight was going on, you accounted for the nine (9) hostages, you tasked a couple of your soldiers to bring the hostages far from the encounter site into a hidden ravine and told them to guard and never to give up the hostages whatever happens as the firefight continues in the background.

All this time, you were giving orders shouting, “Alfa Company maneuver left!”, “Bravo Company maneuver right!” supposedly maneuvering them to the positions where the enemy were. This was to give the impression that there were many raiders. But the initial assault involved only a very few.

Lieutenant Abubakar with his platoon as they joined the fray and, in the end, his trainees were tasked to burn the huts before you finally withdrew.

With the hostages in your possession, you decided not to pursue the enemy any more or even to search the premises for firearms and count the number of enemies killed. You ordered a retrograde, knowing you had already accomplished the most important part of the mission. While the huts erupted in flames, ammunition were exploding. The enemy were not able to sustain the firefight because most of them, as mentioned earlier, have left their ammos inside their huts. The action took the rescuers about 15 to 20 minutes to execute the actual rescue.

After you got the nine hostages, to include the bishop, into safety, you called your battalion commander and saying, “Sir, kuha ko lahat – walang aray!” (Sir, I got them all, no pain!); meaning: no wounded, no KIA! There was massive celebration at the Tac CP in Cayamcam – like cheering for a team who just won a championship fight.

Everybody later found out from the hostages that the bandits just arrived a few minutes from that long 4-day walk when your team appeared.

You never really took time to count how many were the enemies’ casualties or enemy’s weapons left. You just felt after the recovery of the hostages and decided you must disengage quickly knowing that you already have accounted for all the hostages; and expecting that the MNLF reinforcements were coming soon. The main group did arrive a few minutes after you left the burning camp. Massive firing of weapons. Perhaps in anger or to thwart away the demons causing a calamity, like the fire inside the camp (a Muslim belief). You cannot engage the main group because of the hostages who were already with you. All of you were not far from safe yet…

That creek, once a mere feature on a map, had become the artery of their escape—a twisting, treacherous lifeline. In the hours that followed, you would continue your march under cover of night, guided by stars and the silent bond formed through shared peril. But the memory of that frantic dash through water and jungle would stay with you forever: a symbol of the chaos of war, the will to survive, and the unbreakable spirit of those who fight side by side.

There were no sights of blood and overbearing drama, prolonged firefights, hostages being shot and killed. Those things were missing. for the MOV Board to be convinced about the bravery of you Boy; but the objective was accomplished despite the odds of entering huge MNLF camp (I do not wish to compare but just to make a point – look at what happened to SAF44 at Mamapasano). It looked too easy, for the SouthCom commander to exclaim and telling you, “Naka-tsamba ka Boy ha! sabsay abot ng pang-inom para sa tropa” (You were lucky at the same time giving an envelope saying – for the boys). The operation went smoothly rescuing all the hostages unharmed.

That was the case because you believe there was Divine intervention – the presence of the bishop or God protecting you and your troops. In combat operations, it typically refers to a belief or perception that a higher power (e.g., God or a deity) has directly influenced the outcome of a battle or military operation. This idea can manifest in several ways: 1) Miraculous Protection or Survival: Soldiers or commanders may believe they were saved from harm due to divine will, such as bullets missing them, surviving against overwhelming odds, or enduring harsh conditions; 2) Strategic Favorability: Unexpected weather changes, enemy missteps, or sudden opportunities are sometimes attributed to divine favor rather than chance or human planning; 3) Moral or Religious Justification: Some leaders claim divine support to legitimize a war effort, motivate troops, or justify actions taken during combat; 4) Psychological Impact: Belief in divine backing can boost morale and resilience, creating a powerful psychological edge, especially in desperate or difficult situations.

Let me count your blessings, why the Lord has plans for you:

1) When there is no other hope for you to get to college, the Good Lord chose you to pass the PMA exam. You were the only passers in Davao that year.

2) You went down the Pantabangan Dam in a 6×6 vehicular accident that killed four of your mistahs, during your yearling year.

3) You survived your six-year tour in combat with no injuries, but afflicted with Falciparum malaria and near-death ambuscade.

4) You had a stage-4 cancer – GIST (Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor), a rare type of cancer that starts in the digestive tract’s connective tissues, in your small intestine.

5) The Negros governor assassination, where you were invited to attend that Saturday meeting, but you went home to Cebu for your grandson’s birthday.

6) You underwent a major TURP-Prostate , or transurethral resection of the prostate, which was a surgical procedure to treat an enlarged prostate (Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia) by removing excess prostate tissue that blocks urine flow.

7) You overcame five times of pneumonia.

THE RETROGRADE

There, among the fallen branches and scattered supplies, they found Bishop Escaler and the other hostages — alive, though weak and exhausted. Their feet were swollen from days of marching. They were hungry, sleep-deprived, and dehydrated. But they were free.

Getting them out of the jungle was a new challenge. The bishop and his companions had to be carried and helped down narrow trails, through slippery ravines and steep paths. It took nearly five hours to bring them to a point where the plan to land helicopter came at around 3 or 4PM. As darkness fell, the sound of rotor blades cut through the evening air, and the group must be airlifted out to safety.

Your 8-man team led the withdrawal, followed by the hostages, and then 1Lt Abubakar’s platoon in the rear. You decided to take a different route, as you recalled your Scout Ranger Orientation Course, “Never take the same path” – by following and wading in the river to help hide your tracks. The withdrawal was very slow as the bishop was not anymore in his prime and very weak due to hunger and several days walk. You suggested to the bishop that your men can carry him on stretchers and hoping it would hasten the movement, but the bishop refused. He said, “I will walk, I will walk”.

After gaining distance from where you came, you called for a halt and rested. You watched the nuns as they hungrily scrambled for hard “tutong” (burnt) rice from the soldiers’ pots. There was nothing they could give them as the soldiers are out of provisions also; but they always have water from the river to sustain them.

After about ten minutes of walking, a huge volume of explosions and firing can be heard behind them from the burning MNLF camp. They assumed the reinforcement, the MNLF main group, has arrived and opened fire. Muslims believe that gunfire can drive away evil spirits or “kamalasan” (bad luck) or calamity, while their camp was burning. They’re also probably very angry and seeking instant revenge! (MNLF revenge came after ten years, when they deliberately massacred and raided the town of Ipil. The MOV Board does not know that the candidate for Valor rescued the bishop inside the stronghold of the kidnappers, as they retaliated 10 years after.)

You have to move everybody as fast as they could so that you can lose your potential pursuers, as the situation became reversed. The hunters became the prey. You had to reprimand the nuns to refrain from reciting their rosary loudly while they’re silently withdrawing, as you considered the recitation as recognizable noise in the eerie silent jungle. You scolded the 3 women and told them that their “Hail Mary” will get them killed instead.

During the withdrawal, the bishop noticed that some of the soldiers were carrying packs that belong to the kidnappers which was a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for them to check for evidence or clues later. This probably became the basis for the bishop to mention in later homilies that the rescue was orchestrated and not real because he saw soldiers carrying the same packs he saw carried by the kidnappers; but he later found out he was completely wrong. The hostages also told in their testimonies that when and if they were not rescued, they were to be separated that night and be raped.

THE CHOPPER PICK UP

On or about 1530H, Colonel Sangalang called you up and said “Boy kukunin ko yun mga hostages!” (Boy, I am going to take the hostages from you!)

The retreating forces were still in the middle of the jungle and very far yet to their basecamp. You told your battalion commander, “Sir, hindi ko naman papabayan mga ito!” (Sir. I will not take them for granted). However, Colonel Sangalang explained, “Hindi! Malakas at malaking grupo ang nandyan; kapag na engage ka, puede tamaan pa ang mga hostages; at puede pa ma casualty kayo; at hindi mo na ma control ang situation; andyan pa sila prinoprotectahan mo habang nakipag-engage ka pa!” (No! There is a strong and large enemy group there; if you get engaged in a firefight, you can be hit, to include the recovered hostages becoming casualties; you might not be able to control the situation – you are there fighting and protecting them at the same time).

Hence, you replied, “Sige Sir! Kunin ninyo!” (Okay Sir! You can take them!)

There was no landing zone in the middle of the jungle. You found an opening along the creek. It was sandy but flat enough for one Huey to land. You said that you would ignite a red smoke grenade. It was already past 1600H. The smoke would be still visible in the fading daylight. When the chopper was navigating its landing, the rotors hit some bamboo trees. The pilot decided not to land. It was getting dark. You radioed and talked to Colonel Sangalang on board the Huey, “Sir, maghanap kayo ng safe na landing area from here na malapit lang at kami ang pupunta sa inyo!” (Sir, look for a landing area near here and I will be the one to approach you). You were thinking, “Paano yan? Padilim na? Hindi ko alam kung nasaan na ako sa mapa? Gawan natin ng paraan!” (How can that be? It is getting dark. I do not know anymore where I am in the map? Let’s find a way).

Before 1900H, the two Hueys were able to land on top of a hill. The radioman on the chopper told you that they were able to land already. You whispered through the radio, “Sir, paputok kayo ng tatlo!” (Sir, fire a rifle three times!) That was the only way he thought he can find the Hueys . . .PAK PAK PAK . . . everybody in the group was pointing at the same direction where the sound was coming from.

The group moved quickly while dragging the rescued hostages. They were afraid that the enemy might have heard the shots and to include the noise of the Hueys. The MNLF might have detected already the location where the sounds are coming from.

You contacted the Huey again and told to fire three shots again. The sound was getting closer. You were aware that your actions were really very dangerous because the enemy might have heard earlier the first shots. Even the landing of the Hueys might have been sighted by the enemy already. They must reach the chopper ahead of the enemy. Likewise, there were only very few people guarding the Hueys. “Tara na! Bilis!” “Sir last na putok!” (Let’s go! Fast! Sir, fire again for the last time!) PAK PAK PAK . . . You reached the top of the hill but cannot see any choppers! You had only two companions with you. You left the rest of the group with the hostages a few meters behind. You crawled closer and you heard people talking in Ilocano. Huh? You were surprised that the people you saw were not even observing noise discipline. You called out, using your unit’s predesignated call signs, “Maimbung!” Somebody replied, “Bualo! Bualo!” The 2 Hueys were able to land deep in the tall grasses or “Talahib”, camouflaging the Hueys. You were met by Colonel Sangalang asking, “Nasaan ang mga hostages?” (Where are the hostages?) “Nasa ibaba pa Sir! Pasiguro lang.” (Still downhill, just to make sure), as you replied to the question. You greatly admired the skills of the pilots! They were able to land the Hueys without knowing the conditions of the ground. The lead pilot was Captain Nonie Natividad, a graduate of Class ’76 of the Flying School. You went back to usher the hostages. Yourm men were pushing the hostages in going up the hill. When the captives recognized Colonel Sangalang, they embraced their savior. However, You Boy snapped, “Tama na yan pleasantries! Sakay na! Bilisan ninyo! Alam nila nag-landing kayo dito!” (That’s enough pleasantries! Board the chopper! Make it fast! The know that you landed here.). You told the pilot, “Sir balikan mo kami ha?” (Sir, come back for us hey?) but the pilot replied, “Sorry Boy! Wala na kaming gas . . . exacto lang pa Zamboanga.” (Sorry Boy! We do not have enough gas . . . we just have enough in going to Zamboanga). However, the pilot let the injured board the helicopter, especially those who fell in the ravine.

The thrum of rotor blades barely rose above a whisper, muffled by dense “talahib” grasses and disciplined flying. The helicopter, painted matte black, flew by skimming low over the canopy—nearly invisible against the moonless sky. Inside, red interior lights glowed faintly, bathing the faces of the crew in ghostly hues.

They were at that moment flying dark—no running lights, no spotlight, no radio chatter. Behind enemy lines, every sound, every movement, was a potential death sentence.

Before the hostage pick-up, looking for a safe landing site, the pilot’s eyes flicked between the terrain-following nothing yet of radar and thermal imaging display, just pain instinct and gut feelings. The jungle they flew over was a patchwork of black and smoldering gray shapes. Somewhere down there, a friendly operative was waving—exhausted, evading patrols, and running out of time.

“Two mikes out,” the crew chief whispered, his voice tight in the comms.

The jungle swallowed all but the most essential noise. The helicopter banked slightly, nose dipping. At the edge of a ravine, just above the troops, if ever there is one – an infrared image would show a faint, human-shaped heat signature.

There. Too dense for taking off. It had to be a hoisted.

The bird slowed to a hover—no spotlight to guide them, just the soft guidance of instruments and pure instinct. Trees shifted violently below from the rotor wash, but the pilot held steady, blades inches from surrounding branches.

The rescue operator clipped in, gave a silent nod, and disappeared into the dark, lowered down through the black canopy. The descent was swift, blind. Branches clawed at his gear. The only sound in your ears was everyone’s own breathing and the faint chop of blades above.

Boots separated from the earth, as they boarded the chopper. A whisper over the mic: “Clear.” The downed operative, who fell in the ravine, was conscious, but struggling. Rescued hostages were already in place their respective seats, inside the chopper.

Above you, the two helicopters took off, compensating for the extra weight. They cleared the high grounds. The crew chief grabbed them, pulling hard, and sealed the door. Inside, the medic got to work in silence, checking vitals and prepping fluids. The pilot banked west—low and fast. Still dark. Became invisible. Behind them, the jungle closed in again. No trace left.

Extraction complete. No lights. No trace. No noise

THE FINAL MARCH

“Let’s go! Alis na tayo!” (Let’s go! Let’s leave!) Your group and Lieutenant Abubakar’s went down the hill as the Hueys took off. You found the river-creek again and followed it downstream. At 0100H, the following day, you set for a bivouac. “First Squad mag bantay muna! Palit after 30 minutes.” (First Squad to act as guard and to be relieved after 30 minutes). The night at the creek was cold and uneasy. The moon, half-hidden by drifting clouds, cast a dim light on the rippling surface of the water. The men moved quietly, each step careful not to disturb the silence of the jungle that surrounded them. The rhythmic murmur of the creek was their only comfort — a reminder that they were still alive, still moving.

You sat with your back against the rock, your body half-submerged in the shallow stream. The cool water eased the sting of exhaustion, but your mind stayed alert. Your M16 Armalite rested firmly in your arms, a cold metal pressed against your chest like a companion that had never left your side. Across the creek, faint silhouettes of ypur men blended with the shadows, some crouched low, others lying flat, their eyes scanning the darkness.

The first squad stood watch, their senses sharpened by fatigue and tension. Every rustle in the bushes, every croak of a frog, sounded like a whisper of danger. Above them, the canopy shrouded the stars, and the smell of wet leaves mixed with sweat and gun oil.

Time passed slowly. When the next squad took over, a few men closed their eyes for short, broken moments of rest. No one dared to sleep deeply. The memory of gunfire, the sight of burning huts, and the uncertainty of what awaited them downstream haunted every breath they took.

You remained still, your mind replaying the day’s chaos — the thunder of the Hueys, the shouting, the Bishop Escaler and the hostages. Yet amid the turmoil, there was resolve. You looked around at your men — tired, hungry, and soaked — but still disciplined, still following every order.

The creek became their silent witness that night — to their endurance, their fear, and their quiet courage in the darkness before dawn.

Before sunrise at 0500H, you ordered to moved out. You were all famished and have to find food. When you got to the clearing out of the jungle, at around 0800H, one of your men saw a farmer near a nipa hut. you introduced yourselves that you are soldiers. You asked the farmer, “Manong ilan ba ang manok mo at magkano ba ang isa sa palengke?” (Manong , how many chickens do you have and how much would you sell them at the market?) “Mga P20 ho” (Around 20 pesos) “bayaran kita ng P30 bawat manok!” (I will pay you 30 pesos for each chicken). The farmer was smiling while dressing two chickens because it was overpriced and he earned money that day. They cook the chicken into “tinola” (chicken broth) with papaya and malunggay leaves. “Manong saing ka ng maraming kanin para sa amin lahat at bayaran ko din.” (Manong, please cook rice enough for us all and I will pay them too). The farmer was paid handsomely. They got rejuvenated after the meal and continued walking towards the main highway where a six-by-six truck was waiting to pick them up. Honestly, you did not know exactly where you were on the map but you knew you were heading for Zamboanga del Sur main highway. You were quite confident you can bring your troop home, as you believed that you had a very good sense of direction those years. The map was of little use inside a dense jungle with no references and prominent features; more so, during the night when visibility was zero.

You reached the highway at 1300H. You were still very far from your home base. Those soldiers who cannot walk anymore (some fell from the stiff climbing) joined in the Hueys. Colonel Sangalang did not join the trip anymore in going to Zamboanga in bringing the hostages during the night of rescue. He went down at his home base and waited for your group oto arrive the following morning. The raiding group was welcomed back by their Battalion Commander, with a wide grin, and with cases of San Miguel Beer Pilsens – no ice, but all in warm bottles.

The whole battalion celebrated like the dickens and got drunk telling their stories of the raid . . .

EPILOGUE: The Bishop Escaler Version

Reference Book: Yuson, Alfred. In the Footsteps of St. Ignatius of Loyola (The Life of Bishop O. Escaler, S.J., D.D.). Jesuit Communications and Ernest Escaler. 2017.

————-

By the time I finished writing the manuscript of my book (The Expired Valor), I stumbled on an article (from Philippine Star webpage dated 27 August 2017) of Alfred A. Yuson – He was announcing the launching of the bio book, “The Life of an Outstanding Jesuit”.

I told myself; I must have that book to cross-check what I have written! So, I wrote by email Fr. Roberto Yap S.J., the President of Ateneo de Manila University that runs the Jesuit Communications, the publisher of the book, requesting for a Courtesy Call and Book Inquiry. I sent a CC (digital carbon copy) to Mr. Ernest Escaler, the co- publisher. Fr. Yap never replied but Mr. Escaler promptly wrote back on that same day I sent my email, telling me: for my interest in the book, he is sending me two complimentary copies…

I got the two books, through Lalamove, delivered on that same date, made by OJ Salubayba, Mr Ernest Executive Secretary.

In the narration of Bishop Escaler about his rescue, I truly believe that Lieutenant Boy Bolo really deserves the Medal of Valor that the AFP turned down. In the book, the author immediately highlighted in his first chapter that the jungle Bolo penetrated was the stronghold of the MNLF that no one dared to enter.

The bishop narrated also the 1995 Ipil Massacre. It is important to mention and connect the Bishop’s 1985 kidnapping to this incident, to let everyone realize the bravery of Boy Bolo. A decade after bishop’s kidnapping, on April 4, 1995, the town of Ipil was devastated by a brutal assault known as the “Ipil Massacre”, where approximately 200 heavily armed militants from the Abu Sayyaf Group razed the town center, resulting in the deaths of 53 people and the taking of numerous hostages.

In page #18 of the book, the bishop said “he had doubts if the soldiers could continue their operation, after the rescue. General Castro said they would continue the pursuit after they rescued us, although I doubt if they would go through that thicket because it’s so hard to get in?” This is a statement of admiration for Bolo in pursuing them in an unknown territory.

The available information from a personal interview with the bishop revealed in the book, some aspects of his experience in captivity, though it does not describe in detail the conspicuous actions of Boy Bolo, itself. I have to read between the lines:

• The Bishop’s mindset during captivity: He described that he was constantly praying and preparing himself for any outcome, “I always have faith in God, that He will not leave us. (Page #9). Perhaps, there was divine intervention to explain for the outcome of the operation; Bolo’s decisions must not be discounted.

• Church Policy: General Castro, the SouthCom Commander, noted that bishops had agreed not to promise anything to kidnappers, as doing so would make other members of the clergy targets (The no-ransom policy of the Catholic Church, in page #13).

• Bishop Escaler, together with eight others, including three nuns, were rescued by army troopers led by Lt. Abubakar and Lt. Bolo after a 30-minute assault on the rebel camp.(according to page #16). Bolo’s name was only mentioned once. Lieutenant Abubakar was a mere platoon leader, who just followed orders from Bolo, his company commander.

• Upon hearing a barrage of gunfire about 2:30 p.m., the bishop’s driver shouted, “The bishop is in this house?” The house was immediately surrounded by military. There were reportedly 1,000 military men in the area, while a team of 40 commandos stormed the camp (according to page #17). The 1,000 men in the area are the Scout Rangers and Special Forces that were inside camp, far away from the encounter site, that Bolo and his men raided.

• At Page #20, the following narratives are: 1) They stopped on that day in a hide-out on a high mountain with some 10 huts which, they were told, was now two days away from the main MNLF camp. (The enemy’s strength is estimated to be company size, composed of 100 to 250 men – due to the number of huts. Likewise, this explained the three Igorot trackers pointed upward that Bolo and his team must climb.

• By then, the captives were almost dropping from sheer exhaustion, dehydration and malnutrition. ‘I don’t know if I could have made the next two days to Kamlon’s camp,’ Bishop Escaler recalls. (this includes the captors, the hostage takers. It explains why the enemy was not able to react. They were caught surprised and ran away. The result was due to the relentless pursuing and running after the kidnappers by Bolo’s team. Bolo is correct by saying, “kung titigil tayo, mawawala na sila!” (If we stop, we will then lost them) Then, the enemy can reconsolidate their forces.

• The nine were made to stay together in one hut while the kidnappers kept watch outside. (This explains why Bolo was able to save all the hostages without casualties)

• “We were just resting. Suddenly, an M-16 was fired and the container of rice was hit and it splattered all over, just close to my head. They are firing, I thought. The soldiers were shooting.” The soldiers, who the bishop later learned numbered some 40, were about to shoot into their hut when the bishop’s driver and the sisters shouted that they were in there and that they would not fire back. This was because Bolo saw the nun and ordered not to shoot; and Bolo showed himself to the hostages and identified themselves that they are soldiers.

• The bishop and his party were ferried to Edwin Andrews Air Base in Zamboanga City on helicopters, but only after they had to trek another three-and-a-half hours to a clearing. This was nighttime already, difficult to tell their whereabouts but Bolo made it possible to locate where the two helicopters landed.

Bishop Escaler wrote his own account of the episode by way of a pastoral letter to his friends and parishioners. He issued the letter from the Bishop’s residence in Ipil, Zamboanga, on March 8, 1985, upon his return to his prelature (shown in pages #21-23).

Dear Friends in Christ; Pax Christi:

Contrary to what from the beginning of our ministry as a bishop in 1976 when we had set as a policy never to write about one’s self but rather on the various works undertaken with your support and only in June and December of each year, extraordinary times call for exceptions. This time, due to the hundreds of telegrams, letters and phone calls that poured in from here and abroad expressing concern over the safety of the 11 of us from Ipil who had been kidnapped from February 22 morning to 25 evening and rescued by 40 military personnel at 2:30 p.m. of February 25th, I thought it best to write this brief and personal comment re: our captivity’ and to say thank you for all your prayers and concern.

The facts are clear enough: at 8:30 a.m. of February 22, 1985, enroute to Zamboanga on the Prelature’s Fiera jeep, 7 armed men with armalites and carbines stopped us on a lonely stretch of highway in Taungawun, Zamboanga del Sur (some 90 kms. from Zamboanga City). We were 11: myself, 2 Sisters, 3 teachers and the rest were prelature workers and students-4 men and 7 women. A bullet fired at our front tire forced us to stop and go with the 9 kidnappers, 6 adults and 3 boys who claimed to be Muslim MNLFs (Moro National Liberation Front).

Two elderly teachers at our bequest were allowed to find their way back to Zamboanga. The rest of us started on 4 difficult days of walking through steep hills and mountains where trails had to be hacked open with bolos and wading most of the time through rocky bed streams, winding through the thickets of forested jungles. For 3 nights we slept on wet mountaintops and river-beds, hounded by mosquitoes and leeches. Three unfortunate fishermen who saw us passing by were shot to death by our captors. Finally at 2:30 p.m. of Monday, February25th, as we reached a clearing of a very steep mountain where the captors had 10 Muslim type bamboo huts as a sub-camp, the silence was violently interrupted by shouting and a barrage of firing from M-16s and Armalites, for 30 minutes. A few bullets landed in the hut where we 9 were resting after hiking for 5 hours. Meliton, our driver, and the Sisters shouted. Monsignor is here-do not fire on our hut!’ We crept through the dirt and rolled down the mountain to a protective cover, while the barrage of bullets continued. None of the 9 kidnappers were caught. Another 5 hours of hiking and wading through the stream-beds culminated in an airlift by 3 Army helicopters to Zamboanga City. Thanks be to God, none of our rescuers were killed or wounded and all nine of us emerged from the ordeal unharmed and unscathed, though terribly dehydrated, exhausted and famished. Four had to be hospitalized. Doctors flew me to Manila on February 26th for medical check-up and rest.

On Sunday, March 10th, I will be back in Ipil to resume our work with our poor people.

Somehow, what enabled us, I think to survive was a spiritual optimism and trust that having placed ourselves in God’s hands and Our Lady’s, sooner or later in God’s own good time we would later be freed or rescued. Hence, during those difficult days, I never heard a word of complaint or discouragement from our fellow-captives. We started off with commending ourselves for the day to the Lord, commented joyfully at the beautiful waterfalls and forest surrounding our walks and thanked God for the handful of boiled rice and salt given us for food. At night, crowded together elbow-to-elbow on beddings of leaves, we would reflect on the day’s forced march and again commend ourselves to the Lord.

We were completely out of touch with the outside world; none of the negotiators ever contacted us. The main camp of their ‘commander’ was still two days’ march from the sub-camp where we were later rescued. However, hints were made to my companions that if the Bishop were to pay a ransom of P300,000′ we would be released.

However, according to an agreement with our fellow-Bishops and priests, should any be kidnapped, no ransom would be paid. Doing so would leave the door wide open for other kidnappings. This I made clear with the Muslim commander who led the captors. Whatever cash we had we willingly gave them-some P5,000 which the Sisters and teachers had with them to purchase supplies in Zamboanga City. Other valuables stolen by the captors were ordered returned by the 24-year-old Muslim commander. No one was touched and harmed. We respected their situation and I think they also respected the calmness of the victims.

I had been queried by foreign correspondents and local newsmen if the whole affair ‘had not been staged’ by powers-that-be who stood to profit from the spectacular rescue operations. Only God knows where the actual truth lies. Suffice it to say that I’m deeply grateful to the Army soldiers who had rescued us and treated us so well, and to their military commanders who plotted the operation; thankful to our Muslim captors for having treated us as decently as the situation called for, and most grateful for all of your prayers and Masses which drew down God’s mercy and protection on all of us.

It is a wonderful and humbling experience to have a ‘second lease’ on life; wonderful, because life becomes more precious and faith more realistic. Humbling, because of concern of friends like you, inspite of the fact that we had never been able to reciprocate your charity quite adequately. One last factor remains to be faced: if the Lord spared us this time, He still must have some work or suffering that needs to be done before the ‘final resurrection.’ I hope we can be equal to that challenge.

My remaining years will always be of thanksgiving and daily prayers for each and everyone of you.

Permit me to quote our Father General’s (Fr. Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S.J.) parting words in his expression of gratitude during the Nuncio’s reception for him in Manila last Febuary 16th:

May I quote the Arabs when thanking their host: “If I could transform all the grains of sand in your garden into poetry, and speak a thousand nights in poetry, I would be expressing my gratitude to you only superficially?”

In Our Lord,

[Signed]

Federico O. Escaler, S.J.

I truly believe, if not for Bolo’s rightful decisions, unselfish sacrifice and conspicuous valor – the outcome could have been different . . .

THE DAY IPIL BLED